Indian society prides itself on how deeply it values family. We speak of roots, traditions, and homes that stretch across generations. But hidden inside this celebration is a quieter, more uncomfortable truth: for many women, home is never something they own outright. It is something they move through, manage, and emotionally sustain, without ever being allowed to fully claim.

From birth to old age, a woman’s relationship with space is defined by transition. She is born into her father’s house. She is married into her husband’s. And somewhere along the way, she is taught that belonging is not a right, but a privilege she must earn through compliance.

The language we use gives this away.

Before marriage, she lives in her mayeka.

After marriage, she lives in her sasural.

Both phrases are relational. Both are borrowed. Neither is hers.

A Life Spent In Other People’s Houses

At her parental home, a woman is loved, protected, and nurtured. But she is also prepared, subtly and constantly, for departure. Her childhood room is not a lifelong space; it is a waiting room. Her independence is encouraged only up to the point where it does not interfere with marriageability. She belongs, but conditionally. Everyone knows she will leave.

Marriage, often described as a woman “settling down,” is in reality a forced relocation. She does not just marry a person; she is absorbed into an existing household with its own rules, hierarchies, and expectations. The house does not adjust to her. She adjusts to it.

She may run the kitchen.

She may raise the children.

She may remember every festival, every relative, every ritual.

Yet ownership remains symbolic. Decisions are inherited, not negotiated. Her authority is functional, not structural. She maintains the home, but the home does not belong to her.

For decades, she lives inside walls she did not choose, sustaining systems that rarely acknowledge her as central.

Motherhood Does Not Deliver Belonging

Even motherhood, often glorified as a woman’s highest role, does not secure her place. A mother is essential, but also endlessly demanded from. Her labour is assumed. Her sacrifice is normalised. Her identity shrinks as she pours herself into others.

She becomes indispensable, but still not autonomous.

In most households, her value is tied to how well she serves. As long as she is needed, she is tolerated. As long as she gives, she belongs. This is not security. It is conditional acceptance.

And then, many years later, something shifts.

The Arrival Of The Nani

Time passes. Children grow up. Responsibilities loosen their grip. And one day, the woman becomes a grandmother.

Not just any grandmother.

A Nani.

This distinction matters.

Children do not say, “We’re going to my maternal grandparents’ house.” They say, “Nani ke ghar ja rahe hain.” The phrase is instinctive, unquestioned, universally understood.

It is rarely Nana ka ghar.

It is almost never Dada ka ghar.

The house finally takes a woman’s name.

This is not accidental. It reveals a cultural truth we rarely articulate. Only when a woman reaches an age where she is no longer seen as disruptive does society allow her emotional ownership of space.

Why Belonging Comes So Late

A Nani is considered safe. She is past the age of reproduction, past competition, past the possibility of asserting herself in ways that threaten hierarchy. She is no longer someone who needs to be controlled.

Her care is welcomed because it is optional.

Her advice is respected because it is no longer binding.

Her presence is cherished because it does not demand structural change.

The same woman who once had to adjust now sets the rhythm of the house. Her routines define the day. Her room becomes the emotional centre. Children gravitate to her without fear. Her scolding carries affection, not authority.

For the first time, she is allowed to simply be.

This is often framed as respect for elders. But it is more accurately described as delayed permission.

The Feminist Problem With This Comfort

There is undeniable warmth in the idea of Nani ka ghar. It represents safety, softness, and unconditional love. But feminism demands that we look beyond sentiment and ask harder questions.

Why does a woman have to age into belonging?

Why must she complete decades of unpaid labour before she is allowed a space that carries her name?

Why is home something she receives only after she has given everything else?

The answer lies in how patriarchy distributes power. Women are welcomed as caregivers, not as claimants. Their presence is acceptable as long as it does not challenge inheritance, authority, or control.

The Nani gets a home precisely because she no longer asks for one.

That should not be comforting. That should be alarming.

Emotional Ownership Is Not Justice

Some argue that emotional centrality matters more than legal ownership. That love, respect, and influence compensate for the lack of formal power.

But emotional ownership without choice is not empowerment. It is a consolation prize.

Calling it Nani ka ghar does not undo the decades when her name was missing from property papers. It does not erase the years she was excluded from decisions that shaped her own life. It does not compensate for the fact that she had to shrink herself to fit into systems built without her consent.

Romanticising this stage risks normalising the injustice that precedes it.

What We Are Really Celebrating

When we celebrate Nani ka ghar, we are celebrating a moment when a woman finally stops being evaluated. She is no longer judged on obedience, fertility, or usefulness. She is allowed dignity because she has already paid the price.

But dignity should not be a retirement benefit.

A feminist reading forces us to see this clearly: if a woman can be the centre of a home at seventy, she was always capable of being so at thirty. Society simply refused to allow it.

Reimagining Home For Women

The goal should not be to ensure every woman eventually gets a home. The goal should be to ensure she does not have to wait a lifetime for it.

A woman should not need grandchildren to legitimise her presence.

She should not have to outgrow desire to gain authority.

Her belonging should not depend on how non-threatening she appears.

True progress would mean raising daughters who are not trained for departure. Marriages that do not require erasure. Homes where a woman’s name is attached to space long before she becomes a grandmother.

Also Read: London thumakda…

Until then, Nani ka ghar remains both a refuge and an indictment.

A tender reminder that in Indian society, a woman’s belonging is still treated as a reward for endurance, not a right she is born with.

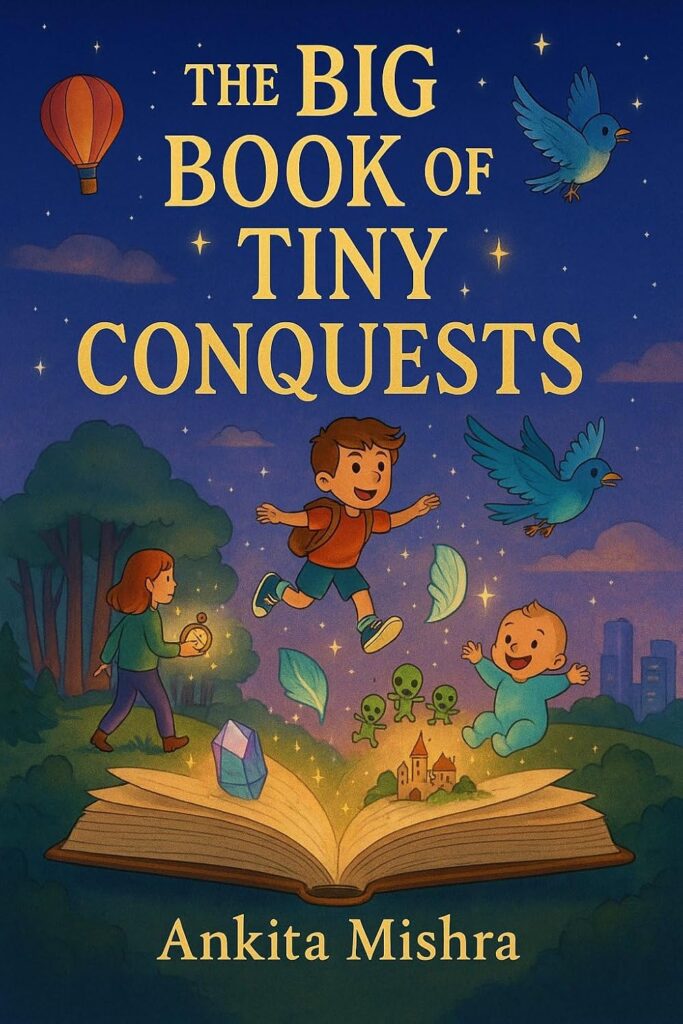

Buy this book to read your Nani ki kahaniyan when you are not around her:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1. Why is the phrase “Nani ka ghar” culturally significant?

Because it reflects emotional ownership. It is one of the few times an Indian household is instinctively named after a woman.

Q2. Is this idea specific to Indian society?

While rooted in Indian culture, the delayed belonging of women exists across many patriarchal societies, expressed differently through language and customs.

Q3. Why is becoming a Nani seen as empowering?

Because it is often the first time a woman’s presence is unconditional, respected, and free from constant expectations.

Q4. Is emotional ownership not enough for empowerment?

Emotional ownership without choice, agency, or structural power is compensation, not equality.

Q5. What would true feminist change look like here?

Women having homes, space, and authority throughout their lives, not as a reward for sacrifice, but as a basic right.